Prof. Kimberly Hamlin, Director of American Studies at Miami University of Ohio, talks to the Boston Summer Seminar about her fascinating archival research for her scholarship on Darwin’s theory of evolution, gender norms, and women’s rights.

*****

We had a very productive second week at the Boston Summer Seminar! Read all about the best archival finds so far from each of our research teams.

Albion College

Degrasse-Howard Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society

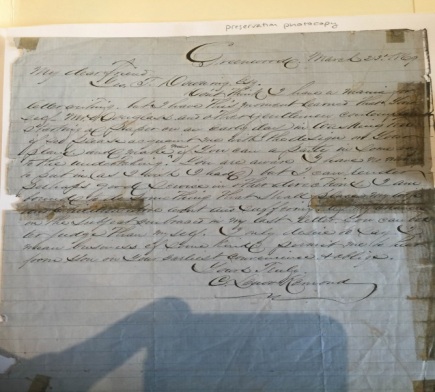

I am researching Northern Black lives in the aftermath of the Civil War. My main goal has been to find anything pertaining to the normal day-to-day life of a black person. One primary source that has been exciting to me is a letter to from Charles Lenox Remond to George T. Downing. The letter was included in the Degraase-Howard Papers, which are located at the Massachusetts Historical Society. George T. Downing was a businessman and civil rights leader who lived in Newport, Rhode Island after the Civil War. Downing and his colleagues had aspired to start a newspaper (which eventually becomes very popular) called the Christian Recorder. In his letter, Charles Lenox Remond tells Downing that he wants to be a part of the paper to “place his life and children’s life above want and suffering.” He says he doesn’t have any money to chip in but would offer his help in any way he can. While the letter was a great primary source, it did not offer much insight into the day-to-day life of an average black person. However, it did make me wonder if the newspaper they discussed would have information on the daily lives of black people in the North. I was excited to find out that I was able to access the Christian Recorder through a database at the Schlesinger Library. The Recorder ended up being helpful because it gave me plenty of interesting information on everyday black life in the north.

~Corey Wheeler

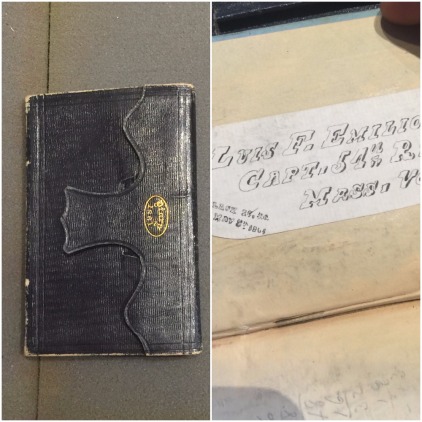

Luis Emilio Papers (Diary and Title), Massachusetts Historical Society

My team and I wanted an opportunity to explore the daily life of the Northern Black population following the Civil War to the end of Reconstruction period (1865-1880). There is a plethora of information regarding the Southern Black lives during this time period, so we wanted to find out more about Northern Black lives. My findings thus far have been scarce but nevertheless intriguing. The New England Freedmen’s Aid Society, which was founded in the North and funded mostly by Northerners, helps shed some light on the schooling system. However, their main focus was educating former slaves and most of their work was done in the South. I also uncovered some information about the 54th regiment, which was one of the first official African-American regiments in the United States and formed during the Civil War. Their Captain was a white man who went by the name of Luis F. Emilio, and I got the chance to look at his diaries. Unfortunately, most of what I am reading is the voice of White America, and as we expected, it’s very difficult to find the voice of Black people during this time period. However, that is not stopping our team, and we are finding some very fascinating information.

~Elijah Bean

Oberlin College

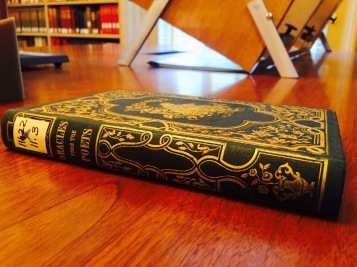

Oracles from the Poets, Caroline Gilman, 1845, Houghton Library, Harvard University

Caroline Gilman compiles poetry quotes in her 1845 book Oracles from the Poets: a Fanciful Diversion from the Drawing Room, re-purposing them as tools of divination. As Gilman specifies in the preface, the book is used as follows: “The person who holds the book asks, for instance, what is your character? The individual questioned selects any one of the of the sixty answers under that head, say No. 3, and the questioner reads aloud the answer No. 3, which will be the oracle” (19). These answers are quotes in verse. The book was gifted to “Mary, from Aunt Lucretia,” in September of 1862 as inscribed within the front cover. Lucretia’s full name, Lucretia M. Fishe, is written in ink the top right-hand corner, with the addition of “-Percy” in pencil, suggesting that Lucretia married before giving the book to her niece. She likely no longer needed it, as the book is a tool for facilitating courtship as well as divination. The question categories are gendered with an eye towards romance, as in “What is the personal appearance of him who loves you?” Often the answers are wry, as with this couplet by Albert Pike: “A beard that would make a razor shake/ Unless its nerves were strong! (73). Perhaps the gentleman in question would read the question to the lady, and she would be obliged to reply in this way, either making him uncomfortable or creating a joke between the two of them.

~Sabina Sullivan

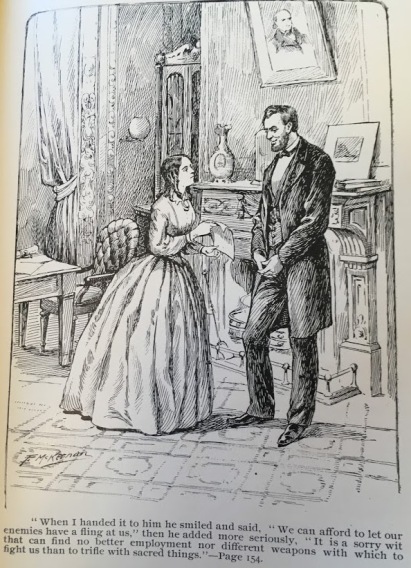

Was Abraham Lincoln a Spiritualist? Nettie Colburn Maynard, 1891, Houghton Library, Harvard University

One of the most interesting publications I’ve come across was Nettie Colburn Maynard’s memoirs, titled Was Abraham Lincoln a Spiritualist? and published in 1891. Nettie was a medium highly trusted by Mary Todd Lincoln, and by association, President Lincoln. As Nettie puts it, “If he had not had faith in Spiritualism, he would not have connected himself with it, and would not have had any connections with it, especially in peculiarly dangerous times, while the fate of the Nation was in peril. Again, had he declared an open belief in the subject, he would have been pronounced insane and probably incarcerated” (93). The spirits embodied by Nettie spoke to Lincoln of the state of the nation in the midst of the Civil War, especially with regard to the Emancipation Proclamation and the subsequent problems faced by freedmen. Although her involvement in the formation of abolitionist policies is not mentioned in most history books, it’s clear that Nettie Colburn has had an impact on the spiritual community in America.

~Amreen Ahmed

Henry Roberts, “Margaret Finch, Queen of the Gypsies at Norwood” (England Before 1790). Courtesy of Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum

There are a surprising number of “gypsies” in Harvard’s archives. They make fleeting appearances across genres and subject headings, stealing into the pages of nineteenth dissertations, plays, poems, newspapers, and trial accounts. They also, of course, appear as the supposed authors of quite a few “Fortune-tellers.” One of these authors is Margaret Finch, “Queen of the Norwood Gypsies,” and author of The little gipsy girl, or Universal fortune-teller, with charms and ceremonies for knowing future events (London 1816), The original Norwood gipsy; or, The fortune-teller’s sure guide, containing easy and simple rules on fortune-telling by cards, and by lines on the hand (Derby 1840), and The New Norwood Gipsy; or Art of Fortune Telling (London, 1840). These three texts establish Finch’s reputation as the “most remarkable Fortune-teller of modern times,” and provide an infallible guide to predicting future events, securing husbands, and close reading of moles, palms, marks, and spots. Her ability to dominate a nineteenth-century literary marketplace for texts that “unlock the secret Cabinet of Fate” is perhaps even more impressive considering the fact that she died in roughly 1740 at the age of 103 (or 108 or 109 depending on the account) and appears to be writing from the grave.

~Danielle Skeehan, Assistant Professor of English

Denison University

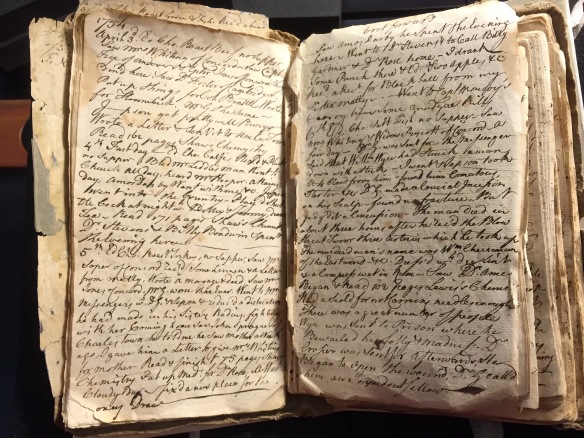

Journal of John Denison Hartshorn, 1752-1756, Center for the History of Medicine at the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard Medical School.

For the past ten days I’ve sat in the Center for the History of Medicine at the Countway Library and looked at some really interesting materials. Take, for example, the Journal of John Denison Hartshorn: it was written from 1752-1756, and most likely ended with his death at the age of twenty. At this age, Hartshorn had done many things that the average twenty-year-old wouldn’t dream of ever having to do – he was an apprentice to an apothecary/physician. All of his daily goings-on he kept in his journal – a document that is now over 250 years old and that I got to hold in my hands. While it may not have been the most useful to my research, Hartshorn’s journal has definitely been one of the most interesting pieces of writing I’ve come across.

~Maggie Gorski

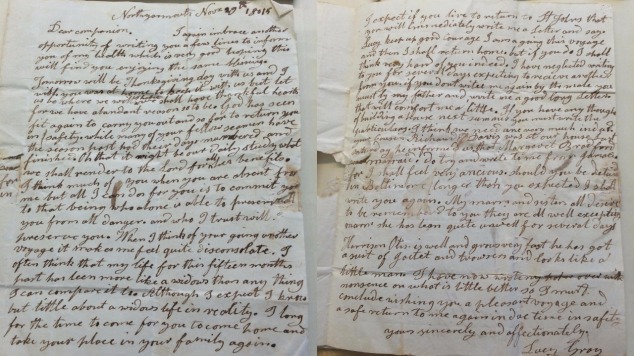

Letter from Lucy Gray to Joshua Gray, November 29, 1815; Letter from Joshua Gray to Lucy Gray, December 7, 1815. Gray family correspondence. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

My portion of the project discusses how separation due to transatlantic travel affected marriage and family life. My most important primary source is the Gray Family Collection at the Schlesinger Library, which includes the family’s correspondence from 1812 to 1848. Joshua and Lucy Gray exchanged letters while he worked on merchant ships and she stayed home in Maine to run the family farm. Their sons later worked with their father; the collection also includes their letters. One highlight of my research so far is a pair of letters from late 1815. Lucy had been parenting a toddler alone for fifteen months. When Joshua told her his homecoming would be delayed, she responded: “my life… has been more like a widows than any thing.” Joshua wrote back that he “long[ed] to be at home” with her as well. Using these letters and others, I will discuss ways the family members expressed longing to see each other.

~Rachael Barrett

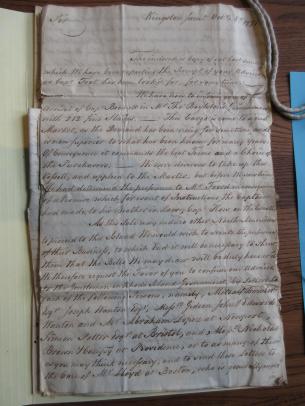

Letter from Eliphalet Flitch, Kingston, Jamaica, to Mr. Thomas Boylston II, Boston, October 8, 1771. Boylston Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

Consensus holds that by the eighteenth century, Rhode Island merchants were the only colonial North Americans regularly engaged in the African slave trade, sending primarily rum to West Africa for slaves for sale to British plantations in the West Indies or South Carolina. A letter from Eliphalet Fitch to Thomas Boylston II, an important Boston merchant engaged largely in the transportation of sugar, molasses and rum from Jamaica to England and the trade of sundries/textiles from England to Boston, suggests that at least one Boston merchant was trying his hand at the Africa slave trade as late as the 1770s. An unnamed ship owned by Boylston had apparently arrived in Kingston with 212 slaves at some point in 1771, prompting Mr. Fitch, Boylston’s agent in Jamaica, to propose the establishment a North American slave trading concern with merchants in Rhode Island. Scraps of evidence suggest that Boylston sent as many as nine slavers to Africa for slaves between 1771 and 1773, but provide no concrete information on the nature or outcome of those endeavors.

~Trey Proctor, Professor of History